During a discussion with a well-known colleague about the state of the art in finance and economics, he observed that we were in a state similar to that of physics during the lifetime of Kepler. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) had realized that planetary orbits were ellipses and had succeeded in describing orbital dynamics by observing that planets sweep equal areas in equal times. Lacking any coherent theory, however, he hypothesized that planetary motion was caused by some motive power from the Sun, which also explained why planets more distant from it orbited more slowly. They were more distant; hence, the Sun exercised less influence.

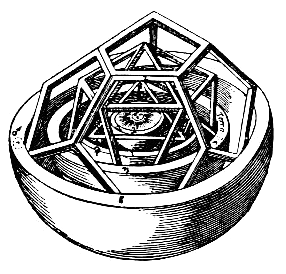

Kepler also modeled the distances of planets by nesting successive Platonic solids within a sphere. With a suitable arrangement, the six Platonic solids accurately modeled the distance of the six known planets. This was a chance correspondence, but he was convinced that he had found a basic law of the universe.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kepler-solar-system-2.png

Kepler’s accomplishments extended to mathematics. His work on the use of infinitesimals presaged the infinitesimal calculus, developed independently by Isaac Newton (1642-1727) and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz (1646-1716). It was not until Newton’s theory of gravitation together with the mathematics of calculus, that a fuller understanding of Kepler’s equal area in equal time law of planetary motion could be realized.

Kepler, however, was intensely concerned with the theological consistency of his theories. His publications include a careful reconciliation of a heliocentric universe with Scripture. He was also a practitioner of astrology.

It is easy from our perspective, to criticize these attitudes. Kepler, however, was a genius. He succeeded in describing and predicting planetary motion more accurately and more simply than anyone had previously. He believed in an ordered universe accessible to human understanding and was committed to the principle that theory must be validated by observation.

One may argue that this is always so. Newton was superseded by Albert Einstein (1879-1955), and Einstein’s theory of relativity has yet to be reconciled with quantum mechanics.But the context here is the effectiveness of theory against the set of tasks that we have set for it. Newtonian mechanics is quite good enough for NASA to send planetary probes throughout the solar system. A comparable level of success has yet to be achieved in economics and finance.

What does all of this have to do with economics and finance? This blog is written from the perspective that these disciplines are in a Keplerian (or, if you prefer, a pre-Newtonian) state. We are committed to the scientific method. We have developed some crude theories that appear reasonable and that have been somewhat validated by actual observation or experimentation.

Unfortunately, we have difficulty knowing exactly what and how to abstract from the complexity of reality to build models which offer us viable predictions. We are constantly blindsided by the deficiencies in our understanding and methodology. These failings are not the Eureka! moments of discovery when an unexpected outcome leads to a new insight, but the fumbling missteps that come from having a not quite clear vision of what’s going on.

We lack an equivalent theory of gravitation to enlighten us. Econo-physics, despite some interesting correspondences, is often just a reformatting of existing results. The foundational homo economicus is not quite right, but not quite wrong either. Behavioral economics and finance seem to describe individual decision making with greater fidelity but materially better predictions of economic and financial events have not been forthcoming. And the mathematical tools we possess are not up to the task. Perhaps developments such as agent-based simulations and cellular automata offer hope, but they are still infants awaiting further development.

This, then, is the blog of a skeptic. Not the arrogant skeptic confident in his criticism of astrology or numerology. It is the blog of the humble skeptic who is all too aware of his dim witted wanderings at the edges of enlightenment.

References

- Bate, Roger R., Fundamentals of Astrodynamics (Dover Books on Aeronautical Engineering), Dover Publications, 1971.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Behavioral_economics, Wikipedia, “Behavioral economics”. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einstein, Wikipedia, “Albert Einstein”. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_Galilei, Wikipedia, “Galileo Galilei”. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_economicus, Wikipedia, “Homo economics”. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infinitesimal, Wikipedia, “Infinitesimal”. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Newton, Wikipedia, “Isaac Newton”. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Kepler,Wikipedia, “Johannes Kepler”. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

Looking forward to seeing where you go with this. A couple of things that I hope you’ll address: what are the limits of a physical analogy when describing human behaviour? And do you think that mainstream economics is really committed to the scientific method?

Great point. I have been thinking similarly for a while now. Avicenna and Medicine might be a better analogy though. Keplerian Physicists at least knew they were looking for something. Modern day economists are more like 17th century medical doctors, gleefully slicing away at stuff, utterly convinced that their crackpot philosophies describe the way the world works.

There are probably many reasonable analogies. I used one related to physics because I felt it would resonate more with both practitioners and academics.

Dr. Frey,

If after more than twenty-five years of careful study and observation, I am hardly any closer to reliably predicting my spouse’s behaviour, I fear this exemplifies the difficulty of the task. Of course, I accept that my attempts may be particularly dim-witted or lacking the required earnest objectivity, and/or my spouse’s behaviour perhaps may too-often be too-far out on [both of] the tails to begin to construct a reliablly-useful distribution. But it does make me *sighhhh* that I have not been able to make better forecasts in this regard….

While I cannot claim to predict my spouse’s behavior, I have been far more successful with my own: It usually ends with me apologizing…

Admire your effort. I’ve noticed over the years that efforts to improve prediction regarding stock and bond prices has yielded nothing. The attempt at a solution has been to throw more math at the problem, which also yields nothing. Perhaps better math can help with economic prediction, I’m in no position to say it can’t. I do know that, in the markets, the quest for better than market returns with the same or less market risk is not achievable.

First, it would mean invalidating the law of risk and reward. Second, anyone who could do it would not only amass near infinite wealth, they’d be a fool to tell anyone else how they did it.

If you can tease out better economic policy, great. Even if it means discovering what is unlikely to work. At least we don’t waste resources on probable failures.

Naturally, improvements have to get past legislators who frequently have irrational agendas, ones that work against the best economics but keep him in office. Building tanks the military says it doesn’t want comes to mind. Other examples abound.

Better math is probably going to be different math. Just as calculus revolutionized mechanics, there is some yet to be developed mathematical theory that will allow us to deal with complex systems. As with the case with calculus, there seems to be some suggestive developments, but how they will mature into something truly paradigm breaking is impossible to predict.

I find it hard to be optimistic that a new kind of math will yield a Newtonian or Einsteinian revolution in finance. I suspect it’s more a problem of data: there just isn’t enough of it and in high enough quality. Current mathematical techniques seems to do pretty well when there are rich, high-quality data sets (i.e. tick-level data). This isn’t a strongly held position, and I’m speaking from the layman’s position of abject ignorance.

Sir – I’m sure you have got many curious. Looking forward for more.

Good piece, but I am not convinced by the main argument. In natural siences, uncertainty is the result of the lack of understanding the laws of physic, which are constant. In the case of economics, however, we cannot assume that there are similar fixed rules. Economic processes by nature are the result of individual intervention, which are simply not possible to predict. The article suggests that this is not so, and although we cannot yet pinpoint them, iron rules of human action similar to that of laws of physics exist, and once we find a proper methodology, ecnomics will become a hard science like physics. This is the naturalist fallacy haunting social sciences for quite long – it would be timely to get for once and all get rid of it.

My main argument is that we can’t make predictions effectively. This isn’t because the problems we are dealing with are stochastic. There are many stochastic systems that we understand well and predict with a high degree of accuracy. Naturally, those predictions are in the form of conditional probabilities rather than a single number, but there are nevertheless good predictions. In finance and economics we don’t yet know how to do that.

My thoughts parallel Visitor above, that physics may have a certain Platonic reality not possessed by economics. Hence the achievements of physics could not be replicated in a subjective discipline such as economics.

But what if the universe does not possess this reality, and it is just that out ability to model physical processes has had a few hundred years’ headstart ??

Don’t take my analogy too far. The solution, when it comes, will not resemble the solution realized by Newton for astrophysics. It has to be something new and unimagined; otherwise, we would already have the tools at hand!

Pingback: Weekly Wisdom Roundp #197 – May 13th 2013 | The Weekly Roundup

I would offer (possibly) that while admire this blog immensely, might not the task it sets for itself “suffer” from a hedge fund manager bias of focussing on prediction?

It seems to me that the tasks Economics should set for itself should be to eliminate human misery and the impediments to human development caused by economic factors — eliminate sovereign debt, unemployment, business cycles, poverty, lack of proper sanitation, etc . . .

Prediction would play a role from the standpoint of coming up with better models for how various proposed approaches at intervention would succeed at this task . . .

I also suggest that the state of Economics could be described (humorously) as Anatevka-ian . . .

If things are pre-Keplerian, how have we kept our balance? Tevya explains it clearly in this vignette:

Pingback: chaussure nike tn

Pingback: オークリー サングラス